- Home

- Timothy Fuller

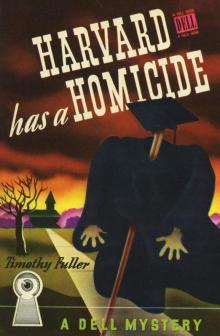

Harvard Has a Homicide Page 7

Harvard Has a Homicide Read online

Page 7

“What do the police think?”

“You can’t tell.”

“Let me see that paper when you’re through.”

“They’re all the same; they don’t know anything, either.”

“You know, I saw this queer-looking guy wandering around outside the House about seven last night.”

“Yeah, sure you did. I suppose he had a knife in his hand.”

“I saw a woman come out of Singer’s entry about six-fifteen.”

“Why not? It was ladies’ visiting day; there were women in every entry.”

“Not like her.”

“Shall we send for the police to get your story?”

“Oh, shut up!”

By nine o’clock every student and most professors had become amateur detectives. Rankin had had eighteen telephone calls reporting eighteen different types of people seen near Hallowell House between six and eight. They ranged from public enemies to scrubwomen. He listened patiently at first, then refused to talk to anyone. He investigated them all; they proved nothing.

In the admittedly exclusive clubs along Mt. Auburn Street and its environs the talk was richer, but much the same. They were apt to take it lightly: —

“Of all the rotten breaks! I have to be in town when all the excitement was out here last night.”

“It was dull.”

“Who is this guy Singer? I never heard of him.”

“If you took a few courses outside of Economics you might.”

“By God, look — old Jupiter found the body!”

“You keep right up with the news, don’t you?”

“Hell, I just got up.”

“I’ll bet he went out and got stunk right afterwards; he’s always looking for an excuse.”

“He probably did it from boredom. I think that’s the only thing he’s never done.”

“What?”

“Killed a guy.”

“It’ll probably turn out to be a publicity stunt by the Lampoon.”

“Hell, no! They’d never have thought of it.”

“I don’t see how we can go to any classes to-day, do you?”

“Certainly not.”

“I’m not going to another class until the murder is solved.”

Later in the morning a well-known professor met a class of inattentive newspaper-reading freshmen. He said: “Gentlemen, a terrible thing has happened. It is a shock to the University and everyone connected with Harvard, but there is no reason why we should not continue our studies in a sane and normal manner. However, as you will undoubtedly continue to view this tragedy as a Roman holiday, I am going to take the precaution of dismissing this class. Good day, gentlemen.” Jupiter woke early. The Chapel bells were announcing the fact that nine-o’clock classes were getting under way. He stretched, yawned, and put his hands to his head. As always, he was surprised that it didn’t come off and roll onto the floor. Once he’d had a dream that he was holding his head in his hands and looking down at his horrible rolling eyes; he’d never quite recovered from it. His tongue made an experimental trip around his mouth and he was pleased that it encountered no pigmies. He was suffering a mild hangover.

Sylvester was making soundless noises in the other room. Jupiter could sense his presence. “Sylvester!” he called. “The master is awake.” Sylvester appeared with a glass of orange juice and a pile of newspapers. The perfect servant. “Good mornin’, Mr. Jupiter. Fine day.”

Jupiter looked out the window. The sun was shining.

“Good morning, Sylvester. If the sun should stay out all day the Transcript will probably have an editorial on the phenomenon.” He drank the orange juice quickly, then reached for the papers.

“Oh, my God!” He collapsed on his pillow. There was a large picture of Singer and beside it a smaller one of himself. It was from his Class Album. “That’s a fine thing to be faced with in the early hours of the morning. They were certainly hard up for news.”

He read one or two stories through and glanced at the rest. No names were mentioned; the stories dealt with the finding of the body, Singer’s educational record, and the arrival of the police. There was not a hint about the Fairchilds. Good, he thought.

“Ah’ll go an’ get some coffee an’ toast, Mr. Jupiter. Is they anything else yo’ want?”

“Not a thing, Sylvester. Hurry back.”

Sylvester went out. Jupiter took a shower and got dressed; he was feeling almost normal by the time his breakfast arrived.

“Any sign of the gendarmes outside?” he asked Sylvester.

“No, suh, but Ah saw the Sergeant go in Professor Singer’s room when Ah went out.”

“Oh,” said Jupiter, sipping coffee, “so he’s on the scene already. I wonder if, he’s nabbed anyone yet. . . . Knock on the door and ask him to step in a minute.”

Sylvester knocked. Illinois opened the door.

“Good morning, good morning!” Jupiter waved. “How’s the world of crime?”

Illinois was becoming hardened to Jupiter’s insanity. “Mornin’, son; you get up late.”

Rankin came in smiling.

“Sit down, Inspector. Have a cup of coffee.”

“You guys sure have a tough life at college,” said Rankin, sitting down.

“This is unusual; only on rare occasions do I allow myself this luxury. The coffee already has sugar and cream, so I won’t ask you how you like it.” He poured a cup.

“You know, I like this scene. I remember a detective story where every once in a while the Inspector would sit down and discuss the case with his confederate. It gave the writer a chance to get in a lot of details he’d left out in his descriptions.” Jupiter was enjoying himself. He hadn’t felt so well in the morning for a long time. “How are things going?”

Rankin laughed. “I’ve never seen anything like it before. You lie in bed while all the rest of the college is out rushing around trying to be detectives. They’ve been calling me up all morning. As far as I can make out, there must have been a parade going by outside here last night, but no one saw anyone come in or out of Singer’s entry. Did anything happen after I left?”

Jupiter looked at the Sergeant intently, but he seemed innocent. “Not a thing, Inspector; I was disappointed. I thought at least there might be a ghost or two roaming around next door.”

“Well, I’ve been over Singer’s room carefully. There’s nothing there that seems to bear on the case, except a letter. Do you know of any woman named Ruth who was intimate with him?”

All is well, thought Jupiter. He pretended deep concentration. “No; I’m sorry, I guess I missed that one. . . . What was in it? Did she threaten his life?”

“No, but it may have something to do with it. What is Mrs. Fairchild’s first name?”

“Constance.”

He said it too quickly. The Sergeant looked up sharply.

“You know them pretty well?”

He was in for it. “They’re friends of my family. I’ve been to dinner there several times.”

“How do they get on? Any trouble?”

You could shave with the tone of his voice, thought Jupiter.

“Why don’t you ask them?” Then he was sorry he’d said it.

The situation was tense. Jupiter tried to ease it.

“I’ve solved Singer’s code message, Sergeant, if that will help.”

“What is it?”

“Notes for his lecture — nothing important.” He described the abbreviations.

When he had finished, Rankin was still serious. “So far you’ve been a great help, Jones. I like you and I’d like to have you keep on helping me, but you’ve got to play ball. So far you haven’t.”

Jupiter was more than curious. “What do you mean?”

Rankin sighed. “I haven’t had your education, Jones, but I know a lot more about police work than you do or than you think I know. I haven’t asked you this before because I was trying to find out myself, but I can’t. Why did you go to the Fairchilds’ house last night?

”

Jupiter blushed for the first time in his life. He felt like a little boy caught playing marbles in Sunday School.

“I guess I underrated you, Inspector,” he said weakly.

“Answer my question.”

Jupiter swallowed. “Mr. Fairchild telephoned me and asked me to come out. Mrs. Fairchild wanted to see me.”

“Had they heard about the murder?”

“Yes, they heard it over the radio.”

“What did she want to see you about?”

Oh hell, he thought, it might as well be the works.

“She wanted to know if I had found her purse in Singer’s room. I had.”

Rankin exploded. “Well, for God’s sake!”

“It was stupid, I’ll admit. I thought it would keep her out of the publicity of the murder. It didn’t. As a matter of fact, I advised her to tell you that she had seen Singer.”

The Sergeant was sarcastic. “That was nice of you. Of course it gave her a chance to make up a good story, but still it was nice of you. All right, now you can tell me the whole story. What was the connection between the Fairchilds and Singer?”

There was no backing out now. Jupiter told the entire conversation between himself and Mrs. Fairchild.

Fie concluded, “I don’t know why I think so, but I could swear that she didn’t kill him, and until you’ve got absolute proof that she did, it’s only fair that you hush things up. You know what would happen if that scandal got in the papers.”

During Jupiter’s talk, Rankin sat perfectly still; now he got up.

“If people weren’t so damn worried about publicity it would be a lot easier on the police. I ought to run you in for concealing evidence, but I’m not going to. You’re just a college boy who thinks the police are a bunch of idiots and that you can solve this murder all by yourself.”

“I’ve changed, Inspector,” said Jupiter.

“You’d better.” Fie was starting to leave. “I’ve told you before, and I’ll tell you again, you can help me if you play ball. As a matter of fact, even though you didn’t hide that pocketbook, I probably wouldn’t have found out the truth about the Fairchilds for some time without your help. You’re in closer to this than I first thought. Remember, after this no secrets.”

Jupiter smiled. “O. K., Inspector, from now on we go hand in glove together. Can I see that letter?”

Rankin thought a minute. “I shouldn’t let you, but you’ve given me some tips even if you didn’t mean to. Here it is.”

Jupiter read the letter for the second time, then handed it back.

“I’ll see what I can do with it, Inspector. What are your plans for the morning?”

“Routine stuff in Singer’s office at the Museum. I’ll see you later.”

He went out. Jupiter relaxed. Sylvester, who had been watching the proceedings with interest, said, “That man there sure is smart, Mr. Jupiter.”

“Smarter than I thought, Sylvester,” murmured Jupiter. “I was under the impression that I was way ahead of him for a while, but now he seems to have closed the gap.”

Sylvester cleared away the breakfast dishes while Jupiter smoked a cigarette. His next move seemed obscure. He could always tag along after Rankin to the Museum and have a talk with Betty. She might have something to offer — mentally, of course.

“You know, Sylvester, there’s an idea roaming around in the back of my head that I can’t place. Something I missed last night. I wish I could catch up with it.”

His reflections were shattered by the telephone. It was Professor Sampson, desiring an interview.

“Well, the day is officially started,” he told Sylvester, getting his hat. “If it continues at the standard set last night, I’ll be a nervous wreck by to-night. Hold the fort.”

He went out.

The rain had annihilated the last of the snow and slush, leaving Cambridge a fresher and happier place. Although he had seen it hundreds of times, the morning sun glistening on the gilt and colored domes made Jupiter aware of the beauty of Harvard’s Houses. Perhaps it’s just as well, he thought, that it does rain so much around here, because when the sun appears it gives such a satisfying shock to the citizens. It was typical of him that he should have these thoughts when his mind would ordinarily be on other things. And it was also typical that he should find nothing unusual about it.

A maid ushered him into Professor Sampson’s study, where he was surprised to find both the professor and his wife. Jupiter thought that she looked as though she had been left too long in a dark, damp cellar and that Sampson himself could do with a sun lamp.

“Good morning, Jones,” said Sampson, offering him a chair.

Jupiter sat down. Up to this point he hadn’t given much thought to Sampson’s reasons for wanting to see him. The way things had gone the night before had accustomed him to anything. He decided to become a listener.

There was a small silence as Jupiter refrained from speech.

Sampson cleared his throat. “This is a shocking thing, Jones.”

He nodded. He felt that by now everyone must be agreed on that point.

The professor went on. “Possibly you may wonder why I asked to see you. We,” he indicated his wife, “are, naturally, stunned by this tragedy. It seems so grotesque, so — so unbelievable happening here in this House, or, for that matter, anywhere at Harvard. I talked with that policeman, Sergeant Rankin, last evening. He was quite reticent in discussing the affair with me, although he appears assured that it was murder. Do you think there is any possibility of — er — suicide?”

“None at all,” said Jupiter.

Mrs. Sampson started to speak. Her husband stopped her. “Just a minute, dear. You’re convinced yourself, Jones, that it was murder?”

“Absolutely,” he said, then he decided an explanation was in order. “You must realize yourself, sir, that Professor Singer wasn’t the type of man who would dream of suicide.”

This time Mrs. Sampson would not be stopped. “How can you say that?” she demanded fiercely. “How can you say that about any man? Your best friend might commit suicide to-morrow and no one would be more surprised than you. You say the type of man! Anyone is capable of suicide.”

“Please, please!” Sampson was trying to quiet her.

Jupiter was dazed. He certainly hadn’t expected this.

Sampson apologized: “My wife, for some reason, is convinced that Professor Singer was not murdered. That’s the reason I wanted to see you, to see if it was absolutely established that there was a murder.”

“Of course,” said Jupiter, “there is a chance that he did kill himself. As a matter of fact, Rankin thought at first that it was suicide, but when he found that Singer’s engagement pad was filled for the next two days and that people had seen him alive and apparently happy at six o’clock, he gave up any thought of suicide.” He turned to Mrs. Sampson. “You must see yourself that if Professor Singer was contemplating suicide he would hardly have seen all those people yesterday afternoon, made appointments to see more in the evening, and then killed himself at half past six.”

It had little effect on her. “I still believe he killed himself — I’m convinced of it! I knew him very well. He was often depressed for days at a time, you must have noticed that yourself. Oh, it’s horrible, disgusting, the police there prying into his affairs!”

She was close to tears.

“Now, Ruth, please be sensible,” said Sampson, going to her.

That was all Jupiter heard. Ruth! Holy God, am I in it again? He stared at Mrs. Sampson. If it was true, it might explain her feeling about suicide, but could it be? How could I have missed hearing about it, he asked himself. God, how cozy Singer must have been! But then, there are hundreds of Ruths loose in the world. How shall I find out? I can’t very well ask her if she wrote that letter. Obviously Sampson doesn’t know about it . . . or does he? This .thing is really getting sticky. What’s the logical way of finding out? Comparing her handwriting, of course, simple Jones. B

ut how? I can’t hand her a piece of paper and say, “Pardon me, but would you care to write a few words? I’m very much interested in chirography.” In mystery stories it’s always done so smoothly; the detective develops a bad hand or something and asks his victim to take notes for him. Hell!

Sampson was still talking. “. . . You’re just upset, dear; this has been an ordeal for all of us. Try and pull yourself together.”

Suddenly Jupiter had a thought. It was too simple. Several samples of her writing were lying in a drawer in his room. Invitations to tea in the Master’s Lodgings — she always wrote them herself!

He got up. “If there’s nothing more I can do for you, sir, I’ll . . .”

The Sampsons did not restrain him.

“Thanks for coming over, Jones. I’m sorry this happened; Mrs. Sampson is not herself.” He shook hands. “I’m sure all this will straighten itself out.”

Jupiter didn’t add that he was doing his best right at the moment.

Going back to his room, he decided that if he witnessed many more scenes of hysterics and weeping he would become unbalanced himself. What is there in me, he asked himself, that makes people lose control of themselves and unburden their souls to me? In the last twelve hours Mrs. Fairchild had wept and told him of a love affair, Hadley had confided his jealousy of Singer, Appleton had made an ass of himself, and now Mrs. Sampson! After this is over, he thought, I’ll have to go out in the country and commune with some placid pigs, if I can find any.

In a messy pile of invitations he found one from the House Master.

There was no question about it — the writing was the same as in the letter.

CHAPTER IX

Harvard Has a Homicide

Harvard Has a Homicide