- Home

- Timothy Fuller

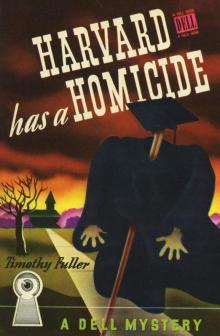

Harvard Has a Homicide

Harvard Has a Homicide Read online

Few people have had occasion to murder a Harvard professor—and yet there was no doubt that Professor Singer of the Fine Arts department had been murdered. He was found dead in his study at Hallowell House by “Jupiter” Jones, an eccentric graduate student who arrived for a tutorial conference. Instead of discussing Fine Arts, “Jupiter” faced the police.

The very first clues appeared to have the makings of two juicy faculty scandals and the Cambridge detective working on the case chose to go slowly. Not so “Jupiter,” who, taking advantage of his familiarity with Singer and his sure knowledge of Harvard, began to piece together the astonishing story. But, like so many amateur detectives, “Jupiter” Jones overlooked a few vital facts.

“Tim” Fuller was a member of the class of 1936 at Harvard. This is his first novel. It is also the first contemporary mystery story to be serialized in the columns of the Atlantic Monthly.

Copyright, 1936,

BY TIMOTHY FULLER

All rights reserved

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

TO MY FATHER

who is a good bookseller and

a fair fisherman

Although some may find it hard to believe, all the characters in this book are both fictitious and imaginary and have no willful resemblance to any persons now living or dead.

Persons this Mystery is about—

JUPITER JONES,

a physical contradiction who looks as if he has just left the hospital after a lingering illness, but who can play five sets of tennis on a midsummer day and come out perspiring only slightly; he is at Harvard for a Ph.D. in Fine Arts, and is sure to receive it with honors, without having tried for anything but plenty of ease and plenty of Scotch.

SERGEANT RANKIN,

a solidly-built man of apparent intelligence and machine-gun type of speech; every cylinder clicks in the sergeant, and his lowly title shouldn’t be allowed to fool anyone.

ALBERT SINGER,

authority on Italian Renaissance painting and a full professor at the early age of forty-five; he is attractive and affected, and his success with women is unusual, although in some cases not unquestioned.

ARTHUR FAIRCHILD,

banker friend of Singer’s, sufficiently wealthy, impressive in evening clothes, whose attractive, energetic wife, Connie, a “Society one,” is, perhaps, an even better friend of Albert Singer’s.

PROFESSOR HADLEY,

that extremely rare character, an absent-minded professor, elderly, and after years of teaching still an assistant, with barely the courage to call his hat his own, let alone his soul, though his knowledge of painting may surpass even that of Professor Singer.

BETTY MAHAN,

assistant librarian at the Fogg Museum, the reason for the influx of students who come, not to study but to look; Jupiter’s interest in her has exceeded the brotherly.

MISS SLADE,

of the Fogg Museum, her identity submerged in that title after twenty-three years at Harvard, fifteen of them secretary to Albert Singer, is a little unattractive gray woman whose only color is centered in the tip of her nose.

FITZGERALD,

a portrait painter, quite famous, “doing” the President of Harvard.

PROFESSOR SAMPSON,

tall, thin, with a narrow face, beaked nose and lined mouth; House Master justly called “The Eagle of Economics,” whose wife, Ruth, appears to have been left too long in a dark, damp cellar.

MR. RENIER,

light-footed little art dealer with offices in Paris, who speaks with what is often called a charming French accent.

HARVARD HAS A HOMICIDE

CHAPTER I

JUPITER JONES threw down the rest of his hand and got up from the bridge table.

“You know,” he said, “it’s time something happened around here. I refuse to play bridge much longer. I want a fire, a riot, and lots of police cars.”

“Have a drink,” said his partner.

“It’s too wet for a fire, March isn’t the season for riots in Cambridge, and one police car is very much like another,” summed up opponent East. “Sit down and play bridge.”

“I don’t blame you, Jupe,” said West; “I feel the same way. If I weren’t going to Law School, I’d leave college now.”

“Everyone says that in March,” said South; “it’s chronic.”

“Hell hath no fury like Cambridge in March or something,” said Jones, putting on his hat. “Well, I’ve got to go down to the House and see the great Singer about a paper I’m writing for him, entitled, ‘Early Northern Sources of Venetian Color.’ It’s a pity you guys don’t study Fine Arts, so you could meet that prince among men. Good night, gentlemen.”

He went out.

“There goes our fourth,” sighed East, “and in a pleasant mood.”

They settled back in their chairs.

West said, “Why is Jones trying for a Ph.D. in Fine Arts? What does he expect to do?”

“He was so attached to Harvard he couldn’t bear to leave after four years,” explained South, smiling.

“You mean he was so attached to that girl in the Museum.”

“Well, maybe.”

“I think he wants to be a curator,” added East. “Why, I couldn’t possibly say.”

“I can’t see him in charge of a museum.”

“I can’t see him in charge of anything except, maybe, a bottle of Scotch,” said South.

“That’s true enough,” mused West. “When does he study?”

“He doesn’t need to.”

“He uses the Jones System, his own fortunately, of starting his week-ends on Wednesday and ending on Monday. Tuesday is his day of work — his week,” explained East.

“Harvard, the Institution of Higher Learning!”

“What does he do all the time?” asked West. “Sometimes I don’t see him for weeks.”

“I don’t know exactly,” answered South. “He has lots of queer friends around Cambridge and I guess he goes off with them or even by himself now and then.”

“He’s a mystery man,” said South. “He knows more people in college than anyone I’ve ever seen; but I don’t think anyone knows him very well, or at all, for that matter.”

East was picking up the cards. He said, “It’s a bad sign when Jones says he’s bored. Something usually happens. I remember one time he said that — a couple of years ago, I guess it was — and the next thing I knew he’d gone in town and collected seven old men.”

“Seven old men?”

“Yes, old stumblebums. Picked them up on the Common and brought them out to his room. Gave them a couple of drinks and took them into the dining hall to dinner — had a special table reserved.”

“My God! I’d never heard about that.”

“The damnedest sight I ever saw — Jones leading that troop. Naturally their clothes were awful. I remember one of them kept wiping his nose on his sleeve.”

“Charming!”

“It didn’t bother Jones. He sat them down at the table and then got up and made a little speech, welcoming them to Harvard — you should’ve seen old Sampson’s face, the Head of the House.”

“Didn’t he get in trouble?”

“Hell, no! He told Sampson later they were the faculty of his old school.”

“Sampson couldn’t have believed that!”

“Of course not; but what could he say? Everything was perfectly orderly.”

“He must be insane.”

“A clean old man,” murmured South.

“I can’t figure it out,” said East. “He graduates with honors without studying, and now he’s getting a Ph.D. the same way. And yet he does crazy things like that.”

“Now he’s talking about

fires, riots, and sudden death.”

“He’ll probably find something.”

“I wouldn’t be surprised.”

CHAPTER II

WHEN Jones left the bridge game and came out on Mt. Auburn Street it was quarter of eight. The chimes, regularly cursed by students living near by, were ending their quarter-hourly concert.

He cursed the chimes and the weather collectively.

Dodging pools of slush, he crossed a street and headed toward Hallowell House.

Edmund Jones was tall, he was thin, and he was slightly sunken; that is, his chest did not expand unless called upon to do so. Some said his face looked haggard, but this was not so. It was just terribly tired. When he sat down in a chair it was hard to believe he would be able to get up again. He did not collapse in a chair, he entwined himself in it. And yet he moved quickly and nervously; his clothes drooping on his body were always neat.

He looked as if he had just come out of a hospital after a lingering illness, but he could play five sets of tennis in a midsummer sun or an hour’s squash in a steam-heated court and come out perspiring slightly. He was a physical contradiction.

Someone, years before, inspired possibly by his heavy eyebrows and condescending expression, had called him Jupiter. Preparatory school nicknames are everlasting. There is no need for quotation marks. Many of his acquaintances did not know his first name; he was Jupiter Jones, whether he liked it or not — and he did.

At the corner he stopped in at Joe’s for some cigarettes. Joe, fat and smiling, was mixing a milk shake for an undergraduate; two others were going through the movie magazines on the stand.

“How’s tricks, Mr. Jones?” said Joe, waving a glass. Jupiter was a good customer — his checks seldom bounced.

“O. K., Joe. Package of Camels,” answered Jupiter, and as Joe handed him the cigarettes, Jupiter asked his favorite question.

“How’s business?”

The answer came as it always did: a shrug of the shoulders, “Oh, you know, same as usual, sometime good, sometime bad, same as usual.”

Jupiter smiled and felt better. Good old Joe, he’s got it down right, same as usual. He looked over the shoulder of one of the magazine readers. A cleverly draped girl stared up at him.

“Steady, boys, steady,” he said as he went out.

Across Mt. Auburn Street away from the Square, you go by dingy two-family houses and tenements and suddenly come upon a House. To a stranger, the transition from the squalid near-slum to the imposing white tower, the even rows of windows, the chimneys, and above all the endless red bricks of a House is startling. After a while you get used to it. You have to. That may be why those old buildings are still there.

Jupiter looked at the clock on the tower of Hallowell House and saw that it was ten minutes of eight. He knew it was ten minutes of eight, but the tower is so placed that when you come to the House from the Square you have to look at the clock. It’s not easy to lose track of the time in Cambridge, even if it is to waste it, he thought.

Hallowell House forms a square. On the east end is the main tower, distinguished from the other Houses by its dome, which is painted orange, a horrid, almost unbelievable greenish orange. Opposite the main tower, across the court, there is another smaller tower which covers the dining hall, common room, and library. There are two entries on either side of the main tower, which read, from left to right, Entry A, B, C, and D. To get to the rest of the building you have to go through an arcade under the tower.

Jupiter lived on the ground floor of Entry B on the left — there are two rooms on each floor of an entry, one on each side of the stairs; there are four floors, making a total of eight rooms per entry. He went to his room, switched on a light, picked up a notebook from the table, switched off the light, and went out. Professor Singer’s room was next to his on the same floor; only a wall separated them, but he had to go outside and into Entry A to get to it. This annoyed him, as it always did.

As he passed Singer’s window he saw it was lighted. Through a crack in the curtain he caught a glimpse of the man at his desk.

“I’ll be right with you, old boy,” he said, opening the entry door.

He knocked on the right-hand door and waited, his hand on the doorknob. Nothing happened. He knocked again, harder. Still nothing.

“Come on, come on, it’s only me — or I,” he muttered. He was getting nervous.

He went outside for another look in the window. Singer was still at his desk, but this time Jupiter saw that his head was resting on the desk. He hadn’t noticed that before.

“Like a light.”

He went back inside and tried Singer’s door. It was unlocked. He went in and walked over to the desk. Singer was leaning forward, half covering the desk, his arms out flat. There was a little blood under his chin. Jupiter touched the back of Singer’s neck with his finger, then sat down quickly in a chair.

Every muscle in his body was twitching. He was shaking, the way he had done one morning in a New York hotel after a four-day week-end, only worse. Much worse. After a struggle he got the package of Camels out of his pocket, but the cellophane licked him. He sank back in the chair. He began to speak; he always talked when he was excited.

“Nerves, nerves, just plain nerves.” His teeth actually chattered. “Thought you were drunk, Singer old man, thought you were drunk. Fooled me completely.” He tried to get up and was surprised that he could. He stood looking down at the man, his mind coming back to normal. He put both hands on Singer’s shoulders and pulled backward. The body came back stiffly into the chair. There was a beautifully wrought gold knife hilt sticking out of Singer’s coat, near his heart. Jupiter let go of the shoulders and Singer fell forward — his head sounded hollow as it hit the desk.

“Good God!” said Jupiter. He sat down again.

His legs felt like old inner tubes and a large lump of iron had just landed somewhere in his stomach. His eyes were starting out of his head. Before, he had known that Singer was dead; now he knew that he had been murdered. Singer murdered! Someone had actually come into this room and pushed that knife into Singer’s heart. God! He hadn’t been such a terrible old guy, after all; but —

“This is no time for sentiment,” he heard himself saying. He reached for the phone and tried to dial Operator. He had trouble getting his finger in the hole.

“Police Department,” he said, and then under his breath, “and don’t spare the horses. . . . Hello? Hello? I want to report a murder . . . I guess he’s murdered. . . . I just found him dead. . . . What? . . . Yes, dead. . . . Professor Singer. . . . Hallowed House. . . . Entry B. . . . No, wait a minute, Entry A. . . . Room eleven — no, room twelve. Yes, that’s it.” He hung up and glared at the phone. “Make sense, please, hell! . . . I suppose you find bodies every day, before breakfast, like newspapers on the doormat.”

Doing something had steadied him. He managed to get the cellophane off his cigarettes and light one. He looked around the room, trying to think of something to do. He thought he ought to look for clues, but he didn’t know quite what a clue should look like. In a corner was a heavy wooden cabinet, obviously antique and Italian, like everything else in the room. Inspiration came to him; he walked over to it and opened a door. Inside was an assortment of bottles. He took out a whiskey bottle and filled a jigger. He had two without looking at Singer. They helped. After all, he told himself, if you’ve known a man as long as I’ve known Singer, you’d be expected to be somewhat unnerved. He guessed the police would be along any minute, so he had another short one, then put the bottle and glass back in the cabinet. He was feeling better. He decided he liked fat, red-faced policemen.

Underneath Singer’s desk, near the edge, he saw a pocketbook. It was a small leather change purse, the kind women carry in their pocketbooks. On it he could see, in neat silver, the initials C. A. F. He recognized them.

Outside he heard the last wail of a siren in death.

He continued to look at the purse, his mind turning over sl

owly like an egg beater in molasses. Then he bent down, slipped the purse in his pocket, and went to the door.

The police had arrived.

CHAPTER III

FOUR policemen came in. Two were fat and redfaced, one was in plain clothes, the other was nondescript. They all wore overshoes. Mr. Swayle, the Hallowell House janitor, hovered near the door, his large eyes and small head moving from one to the other. He was known as the Owl Man.

Jupiter said, “Glad you’ve come,” then, a little dramatically, “There’s the body.”

There was a general babble.

Mr. Swayle said, “Why, he’s dead!”

The plain-clothes man said, “Take it easy, boys.” One cop said, “God!”

The two others grunted fittingly.

“Close the door,” said the plain-clothes man to Mr. Swayle.

They gathered around the desk, looking at Singer. The plain-clothes man repeated Jupiter’s manoeuvre of pulling the body back in the chair. The knife was still there.

“Neat, not gaudy,” murmured Jupiter.

“Knifed!” said one of the fat policemen, and Jupiter liked him for it.

The plain-clothes man let Singer fall forward gently on the desk, then he straightened up.

“You said over the phone he was murdered.” He was speaking to Jupiter.

Jupiter didn’t get it. “I guess I did.”

“What makes you think so?” He was quite pleasant.

Jupiter was still in the dark. “Possibly the knife sticking out of his ribs.”

“H’m,” said the plain-clothes man. He picked up the phone and dialed a number.

The policemen shuffled their feet. Jupiter lit a cigarette.

“Hello! Give me Hennessey.” Pretty soon he had Hennessey. “Hello, Jim. Rankin speaking. . . . Yes, he’s dead. . . . A couple of hours, I guess. . . . I don’t know; it could be suicide.” Jupiter saw the light. “Send up the usual stuff, and, Jim, better have some more men up here. There’ll be a mob when it leaks out. . . . O. K. I will, thanks.”

Harvard Has a Homicide

Harvard Has a Homicide