- Home

- Timothy Fuller

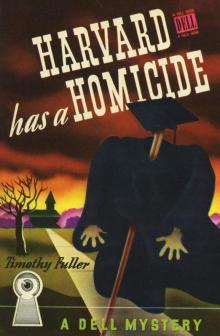

Harvard Has a Homicide Page 4

Harvard Has a Homicide Read online

Page 4

Coming down from the Square, Betty Mahan overheard two undergraduates talking about the murder. She stopped them and asked for details. They were gladly given.

When Miss Mahan became an assistant librarian at the Fogg Museum, the influx of students using that library was noticeable. Officials were at a loss to explain it until Jupiter pointed out that the students didn’t come to the library to study but to look at Miss Mahan. He stated further that, if pretty girls were placed in every library in college, professors would be amazed at the rise in scholastic standing; but that there wasn’t much chance of this, because the supply of pretty girls was limited and all the attractive ones were working in the Deans’ Offices, anyway. Jupiter decided that it was his duty to look after Miss Mahan — his interest had exceeded the brotherly.

“A guy named Jones found the body,” said an undergraduate, concluding his story.

“He did, did he?” murmured Miss Mahan. “Thanks very much for telling me about it.”

She walked off.

“He would find the body,” she told herself. “If there are any old bodies lying around, trust Jupiter to find them, the snake.”

That Singer had been murdered upset her very little, but that Jupiter should find the body and get in on all the fun was too much for her. She was that kind of girl.

“I’ll bet he’s being smug and conceited,” she muttered, “and having the time of his life.”

CHAPTER V

RANKIN had gone back to Singer’s room. Uninvited, Jupiter followed him. Fitzgerald came in with Illinois. Like most good painters, Fitzgerald didn’t look like an artist. He was short, middle-aged, getting fat, and now he appeared bewildered. Rankin said, “What can I do for you?”

“I just heard that Mr. Singer was murdered.” He seemed to feel that that explained everything. “Yes, he was murdered, I think.”

“Well, I — ” He was pretty nervous.

“You said you had something important to tell me.”

“I was just coming to see him and now he’s dead. I mean, he’s dead and I can’t see him.”

“That’s true.” The Sergeant was very patient. “You saw him this afternoon, didn’t you?”

Fitzgerald looked surprised. “Why, yes. How did you know?”

Jupiter felt Rankin had been foolish to mention the visit first.

“I knew,” said Rankin. “And you wanted to see him again. Was he expecting you?”

Fitzgerald tightened. “Yes, he was.”

“What time did you leave here this afternoon?” Rankin asked the question pleasantly.

The artist thought for a minute. “A little after six, I think; I had an appointment to see him at six. I didn’t stay more than five minutes. He seemed to be expecting someone else and he asked if I would mind coming back this evening.”

“You’re sure of the time? You left at five past six?”

“Yes, I should think so. Maybe a few minutes later.”

A strange policeman put his head in the door. “Hey, Sergeant! There’s a lady out here says you want to see her. Name’s Slade.”

“Tell her to wait a minute; I’ll see her as soon as I can.” Then turning to Fitzgerald, “Well, sir, I’m afraid there’s not much more I can tell you about the murder; but if you’ll leave your address I may want to talk with you again. You weren’t planning to leave Cambridge right away?”

Fitzgerald was relieved. “No, I have about two weeks’ more work to do here. I’m doing a portrait of the President, you know. I’m staying at the Hotel Continental, room 303 —you can reach me there. I’m afraid I’ve caused you a lot of trouble coming here, but it was quite a shock. I expected to see Professor Singer, and I—”

“That’s all right; I’m glad you came in.” He turned to Illinois. “Ask Miss Slade to come in now.”

She must have been standing just outside the door in the hall, because Illinois didn’t go out. Jupiter had always thought she looked awful, but he had never seen her look unbelievable. Her gray hair straggled over her forehead and the only color in her face was a bit of red on the end of her nose. She stood in the doorway looking around the room. Then she saw Fitzgerald. Jupiter had seen a lot of movies, but he’d never seen such a look of hatred on any person’s face in his life. He actually tingled.

“Make sure that man doesn’t get away,” she said quietly.

Fitzgerald turned white.

Rankin said, “What the hell do you mean?”

Miss Slade looked at the Sergeant and hesitated, but not for long. “I see you don’t know who killed Singer. He did — just as sure as I’m standing here. I know it and he knows it.”

Fitzgerald coughed. “This woman is obviously insane.”

Jupiter thought for a minute she was going to attack him. The Sergeant stepped closer to her.

“Insane — insane, am I? Not insane and not deaf, either.” She was at least hysterical. “I heard you threaten him this afternoon. Do you deny that?”

Rankin put his hand on her arm. “Please, Miss Slade, just a minute. You’re making a serious charge.” Then to Fitzgerald, “Do you know what she’s talking about?”

“Mr. Singer and I had a few words this afternoon in the Museum which she seems to have overheard. I assure you I didn’t threaten his life.” He had grown much calmer.

Miss Slade had not. “A few words! A few words! You said if he hadn’t made a logical explanation by to-night you would take action — drastic action; and now he’s murdered.”

“Those were my words, I’ll admit; but my action did not involve murder, Miss Slade.”

His tone was level; even Miss Slade was affected by it. She had stopped talking, but was still breathing hard.

Rankin said, “You don’t have to answer now, but I’d like to know what explanation you demanded of Professor Singer.”

Fitzgerald nodded his head. “In view of Miss Slade;’s accusation, I think some explanation is necessary. Some time ago I painted Mr. Singer’s portrait, and I did not press him for payment. He had made no move to pay me and, knowing he had the money, I wanted an explanation. As you doubtless know, artists are always poor. I needed the money, that’s all.”

“That sounds logical,” said Rankin. “I’m afraid Miss Slade was shocked by the news of the Professor’s death. Spoke a little hastily.”

A transformation had come over Miss Slade. She had wilted. Jupiter was sorry for her, but, watching the scene, he felt that she had stepped too far out of character. But then he couldn’t tell; maybe she was inclined to be hysterical. He’d seen her only drifting peacefully around the Museum. He really knew nothing about her.

Fitzgerald was leaving. Rankin went to the door with him.

“I’ll be at the hotel when you want to see me. I hope I can be of some help.”

“Thanks,” answered Rankin. “I’ve been working on this case only an hour and I don’t know where I’m at. I’ll probably call you in the morning.” The artist went out. Miss Slade was sitting in a chair, blowing her nose. Very unattractively, thought Jupiter. The Sergeant went out in the hall. Illinois was mopping his face. There was quite a letdown in the atmosphere.

Rankin came back. “I’ve told those reporters they could go to your room. I want to have a talk with Miss Slade. Don’t tell them anything.” Jupiter took the hint. He almost knocked Sylvester over when he opened the fire door.

“Mustn’t eavesdrop, Sylvester; it’s very bad taste.” He went over and turned on the radio. “The press is imminent. Are we prepared?” Sylvester had whiskey, glasses, ice, and soda ready on a tray. Jupiter went to the door. There were about seven of them.

“Come in, gentlemen, come in,” he greeted them. “It makes cold outside, hein?”

Sylvester was mixing.

One reporter said, “What the hell is this, a murder or a party?”

Another said, “Where’s Rankin?”

“He’s collecting data,” answered Jupiter, “but will join us presently. Keep your hats on, but take off your coats

. The evening is in swaddling clothes.”

Sylvester, inspired, said, “For princes are da glass, da school, da book, where subjects’ eyes do learn, do read, do look.”

A reporter said, “I think I’m going crazy, but I’ll have a drink.”

“Who in God’s name are you?” asked another outspoken scribe.

“My name is Jones; I discovered the deceased,” answered Jupiter. Immediately there was clamor.

Jupiter held up his hand. “Sorry, but my lips are sealed. I am not to talk.”

“Who was the last person to see him alive?”

“What time did he get it?”

“What do you know about his private life?”

“Who was the guy that just came out of there?”

“Who was the old dame that just went in?”

“Was there much blood?”

“Blood?” said Jupiter. “I’ve never seen so much blood. It was ankle deep. They’ve got three scrubwomen in there now mopping it up.”

“Come on, kid, give us a break. What do you know about it?”

“Tell us how you found the body.”

“It was quite simple,” said Jupiter, and he told them his story. He was just finishing when the radio report came on.

“Oh, hell!” said a reporter disgustedly. “ ‘For further details, see your local newspaper’!”

“Radio’s certainly knocked hell out of our stuff.” It was the old complaint. “Everyone knows what the next day’s headlines are going to be.”

“Look what it’s done to advertising.”

Rankin came in through the fire door. They fell on his neck.

“Now wait a minute, you guys; there’s not much I can give you — nothing definite now, no names. Here it is.” Rankin was enjoying himself. “I am fairly sure Singer was murdered. He was stabbed with his own paper cutter, an antique Italian dagger. He was killed between six and eight — that’s as close as I can come now. There are several people I want to talk to. No one’s directly under suspicion. You’ll have to work on that. I’ve got to see Professor Sampson, the head of this building, now. I’ll try and give you some more later.” He went back through the fire door.

“Well, that was a great help,” sneered a reporter. “We knew all that half an hour ago.”

“We’ll have to dig up some stuff on Singer ourselves,” said another. They seemed to be working together. “You can’t expect much more yet.”

The telephone rang. Jupiter answered it.

“Is that you, Jupiter?” said a voice. “This is Mr. Fairchild.”

“Yes,” said Jupiter.

“We just heard about the murder over the radio — shocking.” He was upset.

“Yes,” said Jupiter again.

“It was you who found the — him?”

“Yes.”

“Mrs. Fairchild is naturally very shocked — upset, you know, coming so suddenly. She seems to want to see you.”

“Yes?”

“Do you suppose you could come up? Right away? She says it’s important.”

“Yes, I think I can.”

“I wish you would. Thanks. Good-bye!”

Jupiter hung up.

“Who was that?” asked a newspaper man.

Jupiter thought quickly. “That was my mother. She wanted to know if my laundry was ready. It wasn’t very good, but they took it.

He was putting on his hat and coat. “Just make yourselves at home. Sylvester will look after you. You can use the telephone, if you want to.”

“Where are you going?” Three of them asked the question together.

“I’m going out to buy another bottle of Scotch.”

That held them.

“Tell teacher I’ll be right back,” he said, going out.

“That guy’s a nut,” commented one.

“Just a college boy,” explained another. “Come on, Sylvester, we’ll have another drink.”

CHAPTER VI

JUPITER’S car was parked outside Hallowell House in an alley. He got in and drove out toward Brattle Street. He didn’t know exactly what he expected to accomplish by visiting the Fairchilds, and if the Sergeant found out he would probably give him hell. His father had been a classmate of Mr. Fairchild’s at Harvard, and when Jupiter had arrived as a freshman they had invited him to Sunday dinner. From then on, he had spent a good deal of time at the Fairchilds’. When the food became unbearable at the Union, he would telephone them and they would take the hint and invite him out. They had become quite intimate. After he had graduated and decided to come back as a postgraduate, they had asked him to live with them, but he preferred his own room and of course he couldn’t give up Sylvester.

He thought what a damn fool Mrs. Fairchild was to get mixed up with Singer. Singer, of all people! If she must have her fun, why not someone a little less obvious ? She had been pretty clever about it, though; he doubted if even her husband knew about it.

“Even her husband!” he laughed at himself. “Don’t be dull, Jones! He’d be the last person to know about it.”

He turned into the driveway. The house was set back from the street. It was large and yellow.

“You’ve got some explaining to do, lady,” he said, getting out.

A maid met him at the door. Mr. Fairchild was right behind her.

“Come in, Jupiter, come in. Awfully nice of you to come so soon.” The maid faded out. “This is terrible, terrible! Must have been a shock, finding the body. Terrible!”

“Yes it was, sir — terrible!”

“I saw him a minute myself, this afternoon. Oh, it’s frightful — unbelievable! Stabbed, you say?”

“Yes. Where’s Mrs. Fairchild? I’m afraid I can’t stay more than a minute.”

“Of course. Yes. She’s upstairs. Don’t know what she wants to see you about. Better go up. She’s in the front sitting room.” He waved toward the stairs.

Jupiter expected to find her pale and nervous, but was impressed, as he always was at first seeing her, by her healthy color and tremendous energy. If she was shocked by the news, as she surely must be, she hid it well. A scene from a recent play flashed through his mind. An English mother receiving the news of the death of her two sons as if someone had told her the milk would be late. Why do I think these things, he asked himself.

“Oh, Jupiter, you’re here,” she said.

He sat down.

“Tell me about it,” she ordered.

“Why don’t you tell me about it?” he asked.

“What do you mean, Jupiter?” She seemed sincere.

“Really, Connie,” — she liked him to call her that — “you d‘dn’t ask me to come up here to tell you the gruesome details.”

“Oh, Jupiter, don’t joke now, please.” She was hurt.

“I’m sorry,” he said, and he was. “But I can’t stay long. “What did you want to see me about?

“Were you there when — when the police came?”

“Yes.”

“Did they find anything? I mean, did they find—”

He’d been expecting that.

“They didn’t find this.” He showed her the purse.

“Oh, I’m so glad,” she whispered. “Oh, I’m so glad!”

But that isn’t going to make much difference,” he added.

She stared at him wide-eyed. “You didn’t tell them?”

No, I didn’t tell them,” he answered. “But maybe you’d better tell me how that purse happened to be in Singer’s room.”

I left it there. I didn’t remember it until I got home.” She explained it simply, like a schoolgirl who had forgotten her rubbers. It seemed all right to her now that she knew the police didn’t know.

Listen, Connie, said Jupiter softly. “This is a murder — remember that. I don’t know what you were doing in Singer’s room, but the police will find out you were there. Someone probably saw you go in or come out. They will be up here asking questions. What time did you see Singer?”

You don’t think the

y’d suspect me?” She was beginning to realize the situation. “Oh, if this gets in the papers!”

“They won’t suspect you, and it won’t get in the papers.” He said that to quiet her, “What time did you see Singer?”

“About six, I guess. Just for a minute, though,” she said. “I don’t know — maybe it was later.”

“Try to make sure; it’s pretty important.”

“Let’s see. I got home at six-thirty. I must have left about six-fifteen. I was there only a very few minutes.”

Well, that clears Fitzgerald, thought Jupiter.

“Just for the records, Connie,” — he thought he’d have a try at it, — “did you kill him?”

She glared at him. He had expected a reaction; he got it.

“That’s not like you, Jupiter.” She spoke softly but intensely.

He sighed. “I’m very young and unworldly, but you can’t expect me to miss everything that goes on. I’ve known about you and Singer for some time.”

She broke down. She pulled out a handkerchief and began dabbing at her eyes.

“I’m a fool!” Jupiter realized he was in for it. “I don’t know why I thought no one would know. Oh, Jupiter, you say you’ve known about it, but you haven’t — you’re too young. You’ve read novels about married women with families who make fools of themselves with other men, but it wasn’t like that. Really it wasn’t. I love my family and my husband — I da. My life has been happy; I’ve had everything I want. But you know what Arthur is like; I don’t have to tell you. He’s a model husband, — everyone says so, — but he is tiresome, he really is.” Jupiter agreed with her. “He has no feeling about the things I like; he pretends to like music and painting, but he doesn’t; he hates them. I’ve known Albert Singer a long time; we’ve always been friends. That’s true; really, it wasn’t any more than that. He is — was a charming man. I know you don’t think so, but from a woman’s point of view he was.” She stopped.

Jupiter felt he could finish the story. Why do they always think they’re different, he wondered.

She went on: “We saw a lot of each other, at dinner parties and here — never alone. And then, well, things changed. We went out alone together; lunches in the country — that sort. Oh, you know what happened. It was nobody’s fault — no, I guess it was my fault. I was weak. After that, we had to be careful, and — ” She was crying openly now. “I never loved him, I never thought about divorce. He — he — I think he loved me; he wanted me to divorce Arthur and marry him. I told him I couldn’t — it wouldn’t be fair, fair to Arthur and the children; so I told him it was over.” She sank back in her chair, exhausted. Jupiter watched her; he hated to see a woman cry. He felt inadequate.

Harvard Has a Homicide

Harvard Has a Homicide