- Home

- Timothy Fuller

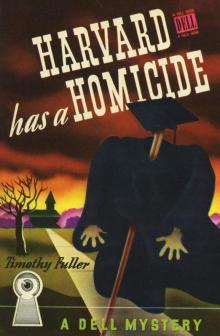

Harvard Has a Homicide Page 9

Harvard Has a Homicide Read online

Page 9

Jupiter was in the dark. “Now what are you suggesting?”

“If he knew she did it, he might try to save her.”

“You think of everything, Inspector,” said Jupiter, impressed.

They were silent while Illinois fought his way through the maze of Boston’s downtown traffic and at length drew up in front of the bank.

Rankin got out. “You stay here,” he told Jupiter.

Jupiter climbed in front with Illinois. “Turn on the radio, Captain, while we wait for the General.”

Rankin sent his name through to Mr. Fairchild and in a very few minutes was ushered into the executive’s office. Like his study at home, Fairchild’s office was decorated almost entirely with pictures of sailboats. The banker arose, shook hands, and offered Rankin a chair.

“I just want to ask you a few questions about last night, Mr. Fairchild,” said the Sergeant, sitting down.

Fairchild held up his hand. “I think I can save you the trouble, Sergeant; I have an idea why you wanted to see me this morning.” He paused and passed his hand over his tanned ‘ forehead. “I should have told you all this last night. I don’t know why I didn’t, except that everything happened so fast I didn’t have a chance to think clearly. . . . Well, what I’m going to tell you is the absolute truth; it will be hard to believe and I hardly expect you to, but nevertheless . . .”

“Suppose you tell me, Mr. Fairchild. I have no reason not to believe you.”

“Of course. Well, I don’t know how much you know about my affairs or what happened last night. Let me start this way: my wife had been having an affair with Singer. I knew nothing about it until last week when she told me. She said then that she had told Singer that she couldn’t go on with it — that is, get a divorce from me and marry him; her home and our children meant more to her than that. As a matter of fact, I don’t believe she ever loved him really — merely infatuated. . . . I am not a brilliant man; I have few interests in life, and those — well, those were not her interests. I can understand her infatuation for Singer, and in a way I can forgive her, but that is beside the point. . . . This past week Singer had been telephoning her regularly, against her will. I decided to see him and put a stop to it. It may not have been my affair, but I decided to make it so. Anyway, last evening, as you know, I went to see him — that was at five-thirty. I told him my wife did not want to see him again and for him to stop making an ass of himself. He told me quite frankly that it was none of my business; that my wife loved him and he wasn’t going to let me or anyone else interfere with his happiness. . . . I am convinced that he was in love with her; for that I can’t blame him, but I told him that she was not in love with him and that he would have to reconcile himself to that fact. He told me that I was mistaken and that I was trying to influence her. By. that time both of us were pretty well wrought up, as you may imagine, and he told me to get out and I did. . . . Well, as I told you last night, I went to my club. There, I thought the thing over and decided to go back and see Singer again to try and make him see my point. I was prepared to do anything to stop him. I want you to know that. By the time I reached his room I had worked myself up to a point where I was prepared to stop at nothing. Without knocking, I walked into his room and there I had the shock of my life . . .”

He stopped. He was breathing as if he had just run a quarter mile.

Rankin waited.

Fairchild took a deep breath and continued: “Singer was sprawled at his desk. I went up to him and saw wet blood near his head; I lifted him up and saw a knife. Then I did a stupid thing, the stupidest thing I ever did in my life: I ran out of that room!”

Rankin did not speak.

“It sounds fantastic, but try and picture my state of mind. I had come to his room ready for anything — no definite plan, except to stop Singer from annoying my wife. And then to find him like that — dead — the shock was terrific! I couldn’t think of anything except that people would think that I had done it. Driving home, I thought the whole thing out and decided to call the police; then it seemed to me to be worse to do that because they would ask me why I hadn’t reported it immediately. . . . I wanted to keep my wife out of it if I could, because I knew if it all came out there would be a terrible scandal.”

“Is that all?” asked Rankin.

“Yes, that’s all, and it’s all the truth — you’ll have to believe me.”

The Sergeant sat back in his chair. “Mr. Fairchild, did you know when you found Singer in his room that your wife had been to see him?”

“No, I did not; young Jones — I mean I found out later that she had been to see him.”

“That’s all right; I know about Jones’s visit to your house,” went on Rankin. “But when you found that she had been there between your two visits, what did you think?”

“What do you mean?” He was perplexed.

“Well, it must have been evident to you that she was the last person to see Singer alive.”

Fairchild thought a minute. “Do you mean did it occur to me that she might have murdered him?”

“Exactly.”

“No, it didn’t,” he said definitely. “You see, we were playing backgammon when the news came over the radio that Singer had been found murdered. My wife fainted when she heard it.”

“Then you had told her nothing about your finding the body?”

“No; you see, I had planned then not to tell anyone. She doesn’t know it yet.”

“It never entered your head that Mrs. Fairchild might have murdered Singer,” mused the Sergeant.

Fairchild got up, his face crimson. “She couldn’t possibly have done it, I know that for a fact! . . . I don’t know how many clues you have found, but you can be sure she had nothing to do with it!”

“You’re asking me to believe quite a lot, Mr. Fairchild,” said Rankin softly.

“Believe what you like of my story, but don’t drag my wife into it!” He was raging, then suddenly he quieted. “I’m sorry, Sergeant; you’ve been very patient. . . .I’m not saying that my wife is incapable of murder, because 1 believe if she set her mind on it she could easily murder someone. But not Singer. . . . I told you she fainted when she heard the news of his death. It was genuine, I assure you. My wife is not an actress.”

“We’ll let it rest at that, Mr. Fairchild,” said Rankin, getting up. “Now if you will tell me the exact time you found Singer’s body, I’ll go along.”

“Let’s see. When I went to his room I wasn’t thinking of the time, but I remember seeing the clock on the tower of Hallowell House. It was about ten minutes of seven — I’m quite sure of that.”

“Thank you, Mr. Fairchild. I wish you had told me all this last night; it would have saved a lot of time.” He was going out.

“You haven’t said whether you believe my story.”

At the door Rankin turned. “Frankly, I don’t know what to believe, Mr. Fairchild. You said, didn’t you, that the knife was in his back?

Fairchild didn’t hesitate. “No, I didn’t say that. It was through his heart, in front.

“Thanks,” said Rankin, going out.

The Sergeant seated himself with a sigh in the back of the car, telling Illinois to go back to Cambridge. Jupiter joined him in the back seat.

“No arrests, Inspector?” asked Jupiter.

Rankin told him of the interview, calmly and without committing himself.

“There’s nothing like a murder to make people lose their heads and do damn-fool things,” he finished sadly.

“Looks as though Fairchild crossed both of us up.”

“That’s just the trouble,” sighed Rankin. “I went in there expecting almost everything and he gave me that story. It’s so improbable that I nearly believe it.”

“Do you still cling to Mrs. Fairchild as the logical candidate?”’

“He doesn’t, anyway,” said Rankin circumspectly. “I don’t know what to make of him; he’s not as stupid as he thinks he is.”

“He’s not s

tupid, he’s just dull. There’s a difference.”

“Well, anyway, it narrows down the time of Singer’s death — we’ve got that much.”

When they got back to Hallowell House they got more.

A policeman met them at the door.

“There’s a student here, Sergeant, who’s been looking for you; says he has something that may be important.”

“Let’s hope so,” said Rankin.

They went into Singer’s room and Jupiter recognized Bob Berrings, an athlete who lived on the top floor of the entry. He looked as if he had just got up. He had.

“You wanted to see me?” asked Rankin.

Berrings’s mind, even while working at top speed, was not a thing to rave over. He said, “Well, I thought I ought to.”

“What about?”

“Well, last night I was out pretty late and I just woke up half an hour ago. That was the first I heard of the murder.”

“Very interesting,” said Jupiter.

“I read in the paper how you didn’t know when Professor Singer was murdered, so I thought I ought to tell you.”

Rankin gasped, “Good God, do you know when he was murdered?”

“Well, here’s what I wanted to tell you. I was writing a report for Singer that was supposed to be in Monday, but I asked him if it was all right if I got it in last night. He didn’t like it, but he said if it was in by six-thirty it would be all right.”

He stopped; the mere effort of speaking was a strain on him.

Rankin waited patiently.

“Well, I finally finished the damn thing at about six-thirty, and you see, I had a date with this girl for dinner. She lives out in Dedham and I was supposed to be there at seven, so I was in a hurry. As a matter of fact, I was a little late, but I had to wait for her, so it was all right.”

He was winded.

“Now here’s what happened,” he went on.

“I brought the report downstairs with me to give to Professor Singer. I guess it must have been twenty minutes of seven by then. I had a little trouble tying my tie, and you know when you’re in a hurry it takes a lot of time. Well, I knocked on the door and nothing happened, so I thought Singer must be in the dining room, so I put the report in his mailbox and went out.”

He smiled triumphantly.

“Is that all?” asked Rankin, dumfounded.

Berrings nodded.

“Anticlimax Department,” whispered Jupiter.

You can check up on the time, because Professor Sampson and Professor Hadley came out of Hadley’s room as I was going out,” said Berrings.

“Well, well,” said Jupiter. “Then you think Singer must have been dead when you knocked on the door?”

“Yes, that’s what I meant.”

“How long did you wait after knocking?” asked Rankin.

“I didn’t wait long, because, you see, I was in a hurry, and I thought of course Singer was having dinner; I just put the report in the mailbox and went out. It’s still there.”

“You heard no sound from Singer’s room? He couldn’t have called to you to come in?” asked the Sergeant.

“No, I’m pretty sure he didn’t,” he said, scratching his head.

“Well, thanks a lot. There’s nothing more you can say that might help?”

“No, I don’t think so.”

“Thanks very much, then. .If you think of anything let me know.”

Rankin ushered him to the door. When he had left, Jupiter said, “That would seem to put the pants on Fairchild’s story.”

“It might, but it doesn’t help his wife,” answered Rankin. “If Singer was dead at twenty minutes of seven, that leaves twenty-five minutes for the murder.”

“Nice figuring; anyway, we’re getting warmer. How about lunch, Inspector? I can’t vouch for the food, but it’s free.”

“Sorry, I’m having lunch with Singer’s lawyer. I’ll see you this afternoon. I’m late now,” he said, going out. “This has been quite a morning.” Jupiter nodded. “Not quite up to last night, perhaps, but interesting, yes.”

CHAPTER XI

WHEN Harvard went to lunch in its various gathering places that day, it was armed with more information than it had been at breakfast. Names were leaking out, speculation was rampant. A group of students who spent their spare time studying and the rest of their time gambling had prepared a sweepstake, using the name of everyone they had heard had been questioned by the police. The drawing was to take place that evening, when it was expected that more names would be available. The news had spread that Jupiter was working with the police.

“You know, I saw Jones in a police car this morning heading in town. I wonder what the story is?

“I spoke to him when he was going up to the Museum. He wouldn’t say a word.”

“God, I’d like to be in his place, the lucky stiff!”

“The Sergeant looks like he knew his stuff. I’ll bet he’ll solve this before Jones.”

“I don’t know. Jones knows a hell of a lot more about what goes on around this place than you’d think, and he wouldn’t mind asking people impertinent questions.”

“Pertinent questions, you dope.”

“You know what I mean. Did you ever hear the story about him in the hygiene lecture? It was his freshman year, naturally, and it was one of the first lectures. There was a new guy giving the lecture and he was pretty embarrassed. He’d been stumbling along groping for words, afraid to say anything definite. Finally it got so bad everyone was fidgeting in their chairs, hardly listening. This guy had got to the point where he was saying something like this: ‘Well — er — as you know, there are women, who are — er — not exactly on our own social level — that is — er — I mean . . .’ Then he stopped for a second and there was a complete silence. Then Jones said in a voice loud enough so everyone could hear: ‘I think what the gentleman means, boys, is “whore,” spelled, w-h-o-r-e. The w is silent.’ God, it must have been wonderful! I wish I’d been there!”

On the way to the dining hall, Jupiter met Peter Appleton crossing the courtyard.

“All is well, little man,” said Jupiter, “I’ll carry your secret to my grave.”

Appleton didn’t look at him. “Thanks,” he said shortly and walked off.

Jupiter shrugged and went into the dining room. He didn’t like to eat in the House, but the rule is that at least ten meals a week must be taken there. You pay for them whether you eat them or not. On top of this, Jupiter felt he owed it to his public to make an appearance. He knew that the reason he was going to eat in the House to-day was because he liked to be stared at and talked about. But, he figured, you can’t be objectionably conceited if you know you are conceited. It was thinking about things like this that kept him awake at night.

He did not, however, want to talk to anyone. So he took a table for two, hoping he could discourage volunteers from joining him. He was disappointed. Adam Rosen, whom he knew slightly, came in after him.

“Do you mind if I join you, Jones?” asked Rosen pleasantly.

“Sure,” said Jupiter. There was nothing else he could say.

Rosen sat down.

Jupiter said, “Did you listen to Fred Allen’s programme last night? It was very, very funny.”

Rosen’s face was a blank. “Well, no, I guess I missed it.”

Jupiter ordered a bacon and tomato sandwich in place of the regular lunch.

Rosen started to speak.

Jupiter picked up his knife. “You know, it’s a funny thing. Why do you suppose they always put the knife and spoon together on one side of the plate?”

Rosen blinked. “I guess you don’t want to talk about last night?”

“Let’s talk about life and — er — ways to prevent it.” It was an old joke, but he felt dull and could see no reason for straining himself for Rosen.

“I was just going to say that Professor Singer’s death will be a terrible loss to the Fine Arts Department. I was taking both his courses, you know.”

“You’re right there, it will,” said Jupiter. “I imagine Hadley will take them over. If he does, they will become very popular courses for those suffering from insomnia.”

Rosen didn’t smile. “It’s too bad, I was just getting interested in them. But Professor Hadley knows quite a lot even if he can’t express himself as fluently as Professor Singer. It will mean more work on the part of the students.”

God, this is terrible, groaned Jupiter. I can’t stand much more.

“I suppose you’ve heard that Colonel Apted killed Singer,” he said, trying to keep his face straight. “Colonel” Apted was the very efficient chief of Harvard’s private police force. His title had been conferred upon him by the undergraduate publications.

Rosen gasped. “You don’t mean it!” Then he smiled. “Oh, you’re kidding.”

“Anything for a laugh,” muttered Jupiter.

His sandwich appeared. It was in record time.

The waitress said, “You’re getting famous, Mr. Jones.”

“The wages of virtue,” he said obscurely.

He ate as fast as he could. There was a long silence, which was even worse than Rosen’s banality.

Finally, in desperation, Jupiter said, “I took Singer’s courses myself. How far had he got in the Venetian painting?”

Rosen brightened. “Well, Monday he finished with the Venetian pageant painters — you know, the Bellini, Cima, and Carpaccio — and yesterday he began discussing sculpture. It’s not really supposed to be in the course, but he wanted to show the relationship to painting. It’s a good idea, too.”

“Yes,” said Jupiter, half listening. “And the course on Rome — I hope that, too, was doing well?”

“Yes, yesterday he discussed St. Peter’s and was going to take up the palaces in the next lecture.”

“Well, well, that’s fine, Adam,” he said, getting up. “And now I must leave you. It’s been delightful.”

Back in his room he collapsed on his couch to wait for Rankin. He could think of nothing to do, and when that situation persisted he usually relaxed. He was almost asleep when the telephone rang. It was Betty.

Harvard Has a Homicide

Harvard Has a Homicide