- Home

- Timothy Fuller

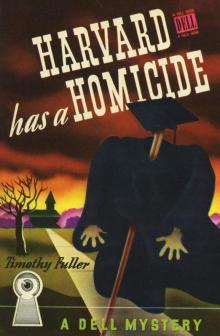

Harvard Has a Homicide Page 11

Harvard Has a Homicide Read online

Page 11

Jupiter stared at the Sergeant with admiration. Rankin went on, “I found out, by asking Hadley this morning if he had heard any sounds from Singer’s room, that Sampson had gone into the toilet at about half past six. Hadley said that he hadn’t heard anything, but that Sampson might have, since he had been in the toilet at that time.”

Jupiter found his voice. “My God, Inspector, you’re a wonder. I’ll have to hand it to you. There’s just one thing that doesn’t sound quite right. If Sampson had planned the thing so carefully, don’t you think he might have put back the glass in the lock so it wouldn’t look as if it had been played with?”

The Sergeant smiled. “That’s the one thing that throws my theory out a little. I thought you’d see that right away. The only way I can explain it is that, after actually killing Singer, he got excited and forgot to do anything about it.”

“You mean ‘there never was a perfect crime’?”

“Well, yes — they always make one slip; but that lock was broken last evening and it’s got to be explained.”

Jupiter frowned. “That’s a very neat theory, but how are you going to prove it?”

“I’ve had the lock photographed for fingerprints and I have a man out to get a sample of Sampson’s and Hadley’s prints. Of course there may not be any prints on the lock if he thought to put on gloves. There were no prints on the knife, but there wouldn’t be, anyway, on a surface like that. You remember how it looked, — twisted gold with those carvings, — not a chance to get a print. Well, the report should be in in a couple of hours and then I’ll know how to go ahead.”

“The old routine,” said Jupiter, delighted. “Cigarette butts and fingerprints. Inspector Rankin gets his man!”

“It’s the only way I know of,” growled Rankin. “And if Sampson’s prints are on that lock, he’s going to have some questions to answer.”

“By the way, Inspector, why did you have me open the lock on this side of Hadley’s fire door when we could have gone around through the hall just as easily?”

The Sergeant laughed for the first time. “I was using you as an experiment. I wanted to make sure how long it takes to open one of those things. I didn’t notice very closely last night. It took you one minute and fourteen seconds!”

“Jones, the human guinea pig. Let’s find another one. I’ll bet I can lower the existing record. When it comes to lock picking I am without peers.” The Sergeant was preparing to leave.

“Well, that’s my theory, and until it’s proved wrong I’m going to stick to it. I’m trusting you to keep it quiet. If the papers got hold of it and then I was wrong, I’d be in a spot.”

Jupiter was just beginning to realize the enormity of Rankin’s discovery. If he was right and Sampson had killed Singer, there really would be some excitement around Cambridge! He could see the headlines: “Head of Hallowell House Kills Professor in Love Duel!” Wow!

“See you later, Inspector,” said Jupiter vaguely, going back to his room.

He went into his bedroom and threw himself on his bed. He could think better lying down. The Sergeant was a canny bird, there could be no question about that. And he wasn’t likely to jump at conclusions. That was obvious from the way he had gone over everyone’s alibi before he had said anything about Sampson.

“But Sampson! Damn it, it’s impossible!” His old habit was getting the upper hand. “Murder’s not in his line.”

He took his pillow and hurled it against the wall. Physical action usually accompanied deep thought.

“What the hell is there to think, Jones, you dullard? A man’s been murdered — that’s the basic principle to cling to. A, a man’s been killed. B, someone killed him. C, there must have been a motive. , D, there must be a method. And finally E, — hell, the grade of my mind. Apply that to Sampson and it works out. But that broken lock still bothers me. With a brain like Sampson’s, he wouldn’t have left it like that. Nevertheless, the lock was broken last night and there’s got to be an explanation. This way lies madness, Jupiter; wait for the Inspector’s fingerprint experiments. But I’d offer even money right now that he doesn’t find any!”

He groaned and turned over. There were so damn many queer things going on. Mr. Fairchild’s finding the body, then shutting up about it. His wife’s purse at the edge of the desk. Miss Slade tearing up newspaper clippings and accusing Fitzgerald of the murder. Mrs. Sampson’s letter and Appleton’s nocturnal prowl. And Hadley forgetting about his dinner date with Singer — on purpose!

“My God, if I hadn’t seen it all myself, I’d never believe it. I wonder if every murder gets as complicated as this.”

He reached down at his feet and picked up the pillow, putting it behind his head.

“Now, Jones, you old detective, you’re going to start from the time when you found the body and go over every minute detail that happened up to the present writing and see if there’s anything you missed.”

For an hour and a half he concentrated. For an uninterrupted period of heavy thought, it set a record. But when Jupiter put his mind on a subject it stayed there. That partly explained his ability to get good marks without apparently doing any studying. There are students who will say: “Well, I worked five hours last night — I know this stuff cold,” and when they are tested on it fail miserably. Jupiter had a photographic memory. He could go over a pile of two hundred slides, the basis of the study of Fine Arts at Harvard, and with half an hour’s study be able to recognize any one of them a month later, giving the name of the painter, his dates, and his school.

When the period of brain exercise was over, there were several points that he felt could stand more explaining.

“I think the person to see is our old friend the Ghost Woman,” he said, getting up. “Hell, if the Inspector can have a theory, I see no reason why I can’t work one up.”

CHAPTER XIII

A TELEPHONE call to Betty at the Museum disclosed that Miss Slade had gone home and was not expected to return. After much difficulty Betty found out where she lived and passed the information on to Jupiter.

In a few minutes he was walking up the murky staircase of her rooming house.

“I’m sure she’ll be pleased to see me,” he muttered. “We shall take tea together.”

Miss Slade opened the door cautiously and looked at him blankly. There was absolutely no expression on her face. He had expected some reaction to his sudden appearance at her home. Astonishment, dislike, fear, or at least interrogation should have been written on her face in capital letters. But there was nothing — just a white face, and an ugly one at that. My God, what a woman, he thought.

“What do you want?” she said in a tone so flat you could lay it on the floor and use it as a rug.

“I just wanted to talk to you a minute, Miss Slade. Do you mind if I come in?”

She said nothing and walked back into the room. He followed her.

“What is it?” she asked calmly.

Jupiter had been ready to ask her a lot of things, but her complete indifference to him had shaken him badly.

He gazed around the dark, unattractive room. Somehow he knew that her room would be like this, devoid of any taste or character. Yet, when he had told Betty that Miss Slade had a dual personality, he believed it to be true, and had hoped for some touch of color in the room to corroborate it. There was none. He decided she was an enigma. Come, come, Jones, he told himself, this is getting you nowhere.

“Did you know that Professor Singer had been planning to retire at the end of this year?” he asked. That question at least would do no harm.

“If you have come here to ask me questions about Professor Singer, Mr. Jones, you will be disappointed. I told the policeman all I know about it and I do not want to discuss it further.”

Her mouth closed with a snap.

Jupiter tried another line. “I’m just trying to find out who killed him, Miss Slade. I think you can help.”

She sighed. “He is dead — there’s nothing anyone can do abo

ut that.”

“That’s perfectly true,” agreed Jupiter. “But aren’t you interested in who killed him?”

“I told you before, I have nothing to say.”

Jupiter was having trouble keeping his temper. “Last night when you came to Singer’s room you seemed fairly sure that Mr. Fitzgerald had killed him.”

She sat down, still with the empty expression on her face.

“Mr. Jones, I think the police are capable of handling everything, I don’t think it’s any of your affair. I would be pleased if you would leave. I am very tired and would like to rest.”

The statement was final. Anyone but Jupiter would have departed, but he had walked all the way to her room and had no intention of leaving until he had finished. He could see she was keyed fairly high and he wanted to say something that would shake her calm.

He took a shot in the dark. “I have been talking with Sergeant Rankin and he doesn’t seem satisfied with your explanation of why you telephoned when you did last night.”

The shot landed. She was staggered.

“I — I phoned about some work I was doing. Is there anything unusual about that?”

Her voice trembled, and for the first time there was a look of fear on her face.

Jupiter followed it up. “But when you arrived at the room you were convinced that Fitzgerald had killed Professor Singer. How did you know that he had been murdered?”

She didn’t hesitate. “I didn’t know he was murdered until I got to Hallowell House. I heard people talking about it.”

“But as soon as you saw Mr. Fitzgerald you accused him of the murder,” he said quietly.

“You were there last night and heard Mr. Fitzgerald’s explanation.”

“And you’re satisfied with that now?”

“I am,” she answered softly. “Now, Mr. Jones, I wish you would leave me. I don’t want to talk any more.”

There was nothing he could do. He smiled and started for the door.

“Thank you very much, Miss Slade. I’m awfully sorry to have bothered you. I know how tired you must be. But I have been under suspicion myself and I’m just trying to help the police.”

At the door he stopped and gave her what he considered his most charming smile. “By the way, have you ever seen Fitzgerald’s portrait of Singer?”

She got up. “No, I never have. Good-bye, Mr. Jones.”

Her cat was massaging itself against her ankles.

He went out and closed the door.

“Net profit of interview, zero,” he told the stairs. “But, reading between the lines, not quite a total loss.”

CHAPTER XIV

JUPITER was taking a shower. After the Slade interview he had decided some exercise would be in order and he had played squash with Bob Berrings. There was still no news from the Sergeant. Sylvester was in the room doing nothing. Jupiter suspected that he was hoping there would be some reporters around for a return engagement with the dice.

“Will you join me in a cocktail, Sylvester?” he yelled through the water.

Another of Sylvester’s less arduous duties was to keep Jupiter from becoming a solitary drinker. Although the risk of this was slight at Harvard, he usually preferred Sylvester’s company to that of thirsty undergraduates.

“Yassir,” answered Sylvester quickly.

Jupiter had slipped into a pair of shorts by the time Sylvester was ready.

“To murder, the liveliest of indoor sports,” he said raising his glass.

They drank. Jupiter coughed.

“What did you make this with, old man?” asked Jupiter.

Sylvester held up the bottle of Scotch that had recently belonged to Singer. ‘

“Dat’s all there was, Mr. Jupiter,” he apologized.

“Well, it’s appropriate, anyway,” he smiled.

They had another while Jupiter dressed.

“I’m going to be at Locke Ober’s for dinner until about eight-thirty, so if anything astounding happens out here get on the wire and tell me about it,” he said, getting his coat.

“You want me t’ stay heah?”

“Yes. Run out and grab a sandwich, but wait around until eight-thirty. The Inspector may telephone.”

Sylvester looked sad.

Jupiter said, “Cheer up, there aren’t any ghosts. Have some of your pals in for a game of slapjack if you want.”

He went out. He got his car and picked up Betty. She had on a neat little hat and coat. She wasn’t quite a blond.

“Lovely as always,” said Jupiter.

“You’ve been drinking,” she noticed. “How hangs the horrible Harvard homicide?”

“How long did it take you to think that up?” he grinned. “The Inspector has a theory.”

On the way to Boston he told her about it. By the time they had reached the restaurant and Jupiter had ordered the meal and cocktails she was up to date.

“And you don’t think much of it?” she said.

“I preserve an open mind.”

“Did you see Miss Slade?”

He nodded. “Reticent is the word for Slade.” They sipped their drinks.

Betty said, “Then if Sampson’s fingerprints are on the fire door, he’s the guilty party?”

“Unless he can talk very fast and convincingly.”

“When will you know?”

“If they’re there, Rankin will probably telephone me. He must have found out by now, but he hasn’t called me.”

“Why don’t you call him?”

“I’m going to in a while.”

They had another cocktail.

Betty frowned. “This is getting us nowhere.

“I find it very pleasant,” smiled Jupiter. “Shall we talk about modern art? Do you know how the school of Dadaism was founded? I see you don’t. They cut out little pieces of tin and paper and tacked them on a canvas. They held an exhibition. One of the leaders stood on a chair and shot himself through the head when people came to the gallery. They thought he was a genius and thus a great new movement was begun. Fortunately it didn’t last long.”

“Why don’t you call the Sergeant?” asked Betty. “You have no soul,” he said, getting up.

He called Rankin and was back in ten minutes.

“I am bewildered,” he said, sitting down.

“Were there any fingerprints?”

“Yes, there were fingerprints.”

“I don’t like to appear inquisitive, you know,” she said dryly, “but whose were they?”

Jupiter cut his steak. “No one seems to know.”

She controlled herself with an effort. “Stop acting like a second-rate amateur detective and tell me about it. Do you want to spoil our friendship?”

“That’s true, no one knows.” He went on eating. “I was hungry — nothing but a sandwich all day.”

“I hate you,” she said, “but it’s not going to stop me from eating your food.”

They ate in silence. Finally Jupiter stopped.

“There were fingerprints on the lock. They weren’t Sampson’s or Hadley’s. The Inspector is tearing his hair.”

“But whose were they?”

“Ah!” he laughed. “A good question. That is the nub. You’ve put your finger on the important print — I mean point.”

She sniffed. “Don’t patronize me. What is the Sergeant doing about it?”

“Hell, what can he do? He can’t go around taking everybody’s prints. He saw Sampson and he admitted being in the john about six-thirty, but he said he didn’t notice the fire door.”

“Do you believe that?”

“Sure, why not? His fingerprints weren’t on the lock.”

“He might have worn gloves.”

“I, too, am a follower of crime,” said Jupiter shortly. “But how about Mr. X’s telltale marks? Sampson and Hadley were in the room from four until twenty minutes of seven. Whoever broke the lock must have done it before or after. We’re fairly sure that Singer was dead before they left the room, so that mus

t rule out anyone killing him via the two toilets.”

“But it doesn’t explain the broken lock.”

“True,” said Jupiter, attacking the salad.

They were preoccupied with eating.

Finally Betty said, “I think Miss Slade knows something.”

“I think she thinks she knows something,” Jupiter qualified.

“The same old psychoanalyst,” sneered Betty. “Aren’t you afraid of Freud?”

He disregarded her. “Let me see that piece of newspaper.”

“I told you I was going to throw it away. Don’t tell me you’re interested in any little thing my feeble mind might work out?”

“Let me see it,” said Jupiter patiently. “Come on, papa won’t buy you any more Scotches and sodases unless you’re a good girl.”

She handed it to him. “I don’t see why you want to see it. There’s nothing except a date.”

He looked at it. “Nothing but the date, but it’s from the Herald ”

She was startled. “How do you know that?”

He smiled condescendingly. “From the type, darling.”

“You’re marvelous,” she cooed. “When I write my memoirs I can say I was privileged to know one of the truly great minds of the twentieth century. So what?”

“So we can find the story that goes with it.”

“Granted that you can find the paper, how will you know what story goes with it?”

Harvard Has a Homicide

Harvard Has a Homicide